The Life insurance premium finance necessitates the policyholder obtaining a loan from a bank to pay the premiums on his or her policy. The strategy works to lower the net cost of purchasing a large life insurance policy, and wealthy Americans use premium financing for this purpose. However, there are times when unscrupulous insurance agents and/or marketing firms attempt to use the core concepts of premium financing to sell life insurance in an extremely risky manner.

What is Premium Financing Life Insurance?

Borrowing money to pay all or part of the premium due on a life insurance policy is something known as life insurance premium financing. Borrowing money to pay a life insurance premium may seem unusual, and it’s certainly not for any old life insurance policy. When someone has a significant need for life insurance, and the cost of that life insurance is always significant, premium financing becomes available.

Consider the following scenario: a wealthy individual discovers that he requires $30 million in life insurance coverage and that the annual premium for such a policy is $900,000. He could pay the $900,000 (remember this because it’s important), but he chooses to approach the problem through his banking relationships. He seeks out a bank willing to lend him $900,000 per year to cover the premium. The individual will pay the loan’s interest and pledge the cash value of the life insurance policy as collateral for the loan. Because the cash value of the life insurance policy will not equal the total loan amount from policy inception, he will need to pledge other assets he owns as collateral to satisfy the bank’s requirements for issuing the loan.

The good news is that he’ll be able to get a loan with low-interest rates. A loan that is linked to either LIBOR or Prime plus a small spread. This means that the out-of-pocket insurance costs will be a fraction of the $900,000 annual premium.

If everything goes according to plan, the wealthy individual will pay off the loan, reach a point with the life insurance policy where he no longer needs to pay premiums, and now own a permanent life insurance death benefit that he obtained much more cheaply than if he had purchased the policy the traditional way. You may notice an underlying implication that things may not go as planned. This can and does happen, so let’s take a look at some of the possibilities.

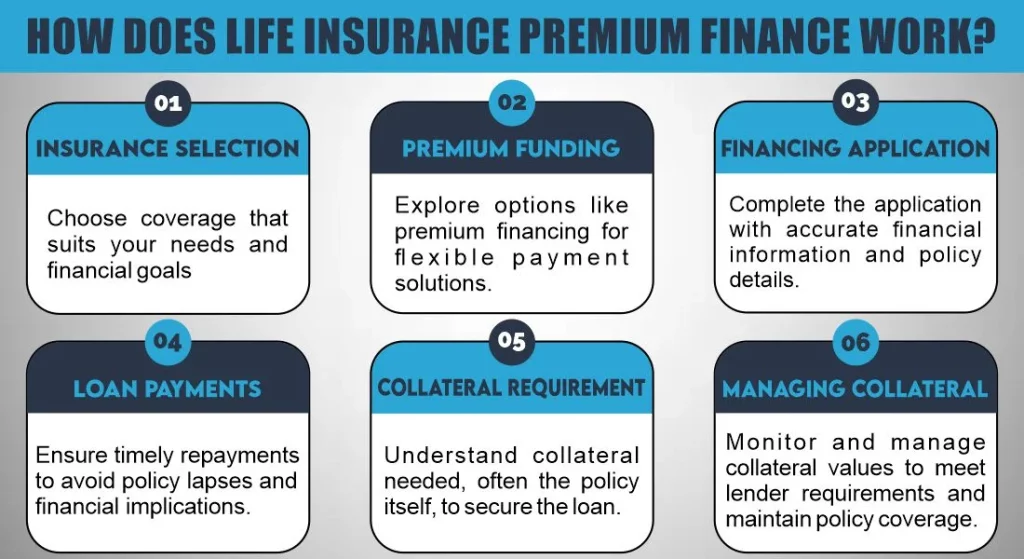

How does life insurance premium finance work?

Life insurance premium financing is a strategy used primarily by high-net-worth individuals, trusts, or businesses for estate planning or retirement planning purposes. Here’s how it typically works:

Insurance Selection

The individual, trust, or business insurance financing decides to purchase a substantial amount of life insurance, often in the form of Indexed Universal Life (IUL) or Whole Life insurance policies. These types of policies are favored because they offer stability and can provide a high loan-to-value ratio (90% or more).

Premium Funding

The policyholder intends to fund the life insurance policies with the maximum allowable premium payments during the initial 4-7 years. This strategy is designed to build up the cash value of the policy quickly and ensure strong long-term performance.

Financing Application

The policyholder may apply for a premium capital finance loan from a third-party lender. This loan is used to pay the insurance premiums. Some individuals may choose to pay the first premium out of pocket to avoid posting collateral, while others will rely entirely on the financing loan.

Loan Payments

Typically, the policyholder is required to make regular payments to the lender, which often consist of interest-only payments. Some more aggressive strategies involve allowing the accruing interest to be added to the loan balance, with the hope that the cash value growth of the insurance policy will outpace the increasing loan amount.

Collateral Requirement

The borrower/policyholder must be prepared to provide sufficient liquid assets or marketable securities as collateral to the lender whenever there is a shortfall between the policy’s cash values and the total loan amount. Properly designed life insurance policies can often serve as a significant portion of the collateral required.

Managing Collateral

In some cases, the policyholder may choose to pay certain early premiums themselves to avoid the need for additional collateral or to simplify the premium financing process.

It’s important to note that while premium financing can be a powerful wealth accumulation and estate planning tool, it also comes with risks, including potential interest rate increases and policy performance variability. Therefore, individuals considering this strategy should do so with a clear understanding of the benefits and risks involved and work closely with financial advisors and experts in the field.

How Much Does Life Isurance Cost?

Benefits of Premium Financing

Premium financing life insurance offers several advantages for high-net-worth individuals, trusts, and businesses seeking estate planning or retirement planning solutions. Here are the key benefits of this strategy:

- Leverage for Wealthy Individuals: Premium financing allows individuals with substantial life insurance needs to leverage their existing assets and banking relationships. This means they can secure a large life insurance policy without the immediate burden of paying the entire premium out of pocket.

- Enhanced Liquidity: By borrowing funds to cover the insurance premiums, policyholders retain liquidity, enabling them to invest their capital in potentially higher-return opportunities. This can lead to wealth accumulation beyond what would be achievable by paying premiums directly.

- Estate Planning: Premium financed life insurance is often used as a powerful tool for estate planning. The death benefit can help cover estate taxes, ensuring a smooth wealth transfer to heirs without depleting assets.

- Tax Benefits: Depending on the structure and purpose of the policy, premium financing may offer tax advantages. Cash value growth and death benefit proceeds are often tax-advantaged, enhancing the overall financial planning strategy.

- Low-Interest Rates: Premium financing typically involves loans with low-interest rates, often linked to LIBOR or Prime, reducing the out-of-pocket insurance costs compared to traditional premium payments.

While premium financing offers these benefits, it’s essential for individuals considering this strategy to be aware of the associated risks and seek guidance from financial experts to make informed decisions.

How to Sell Life Insurance Premium Finance?

While selling life insurance premium finance you have to remember some factors. Here are steps to help you sell life insurance premium finance:

1- Learn About Life Insurance Premium Finance

Before you can sell it, you need to fully understand what premium financed life insurance is. Determine the different types of policies available, how premium financing works, and the risks and benefits associated with it.

2- Get Licensed

In the USA, you need to be licensed to sell insurance. Check your local regulations and obtain the necessary licenses and certifications.

3- Identify Your Target Market

Life insurance premium finance is typically designed for high-net-worth individuals and business owners. Identify potential clients who may benefit from this type of insurance, such as those with substantial wealth and estate planning needs.

4- Build Trust and Relationships

Building trust is crucial in insurance sales. Establish strong relationships with potential clients by understanding their financial goals, needs, and concerns. Listen actively and offer solutions tailored to their specific situations.

5- Educate Your Client

Many people may not be familiar with premium financed life insurance. Educate your clients about how it works, the potential tax advantages, and how it can help with estate planning and wealth transfer.

6- Work with Financial Advisors and Attorneys

Collaborate with financial advisors and estate planning attorneys who can help you connect with potential clients and provide expertise in structuring premium financed policies to align with their financial goals.

7- Address Risks and Concerns

Be transparent about the risks associated with premium financing, such as rising interest rates and policy performance. Explain how these risks can be managed and mitigated.

Changes in Policy or Loan Provisions

The loan rate can fluctuate when financing the premiums of a life insurance policy. Typically, the bank will lock the rate on the loan for the first few years of the arrangement before switching to a floating rate on bank financed life insurance. Some lending agreements also require the borrower to reapply for the loan after a certain period (e.g. 10 years). A falling interest rate is unlikely to be a major issue. It means that the borrower will pay less interest to service the debt than was previously assumed.

A rising interest rate, on the other hand, poses a risk. It is almost certain that the borrower is paying more interest than was originally assumed. This could significantly alter the expected benefit of financing the premiums versus simply purchasing the policy without financing the premiums.

Furthermore, the accumulation feature of the life insurance policy may produce less cash value than originally assumed, which may change the collateral requirements the borrower must meet and/or the timing of the exit strategy. A declining dividend (in the case of whole life insurance) or a change in the index cap, participation, and/or spread rate (in the case of indexed universal life insurance) can all raise the cost of financing the premiums.

What Happens If You Are Unable to Pay Your Life Insurance Premium?

Remember how we described earlier that the individual in our example could simply pay the entire premium? This was something you took note of. When a prospective policy owner can pay the premiums out of pocket but chooses not to, premium financing should be discussed. Premium financing is not a tool used to enable people to purchase life insurance that they would not be able to afford otherwise.

This raises a fascinating question. Is private premium financing life insurance really necessary if someone has enough money to pay a $900,000 life insurance premium with a $30 million death benefit? Yes and no are both possible answers. It is determined by the liquidity of the individual’s assets as well as how he earns his income.

There are undoubtedly situations in which people with this level of income and net worth do not require life insurance. However, there are some situations in which people with this kind of income and net worth desperately need life insurance to avoid catastrophic financial consequences upon death. The critical point to grasp here is the small number of people for whom premium financing will ever make sense.

Finally, if you borrow money to pay premiums and cannot pay those premiums yourself, you are likely to suffer a painful loss. To be honest, the bank’s underwriting process should have discovered this fact and denied the loan. That used to be more reliable than it is now.

Using Premium Financing to Purchase Cash-Focused Life Insurance

As you may conclude that premium financing is not for the faint of heart. Several elements can go wrong and change the overall benefit of the plan. At best, it’s a risky bet for those looking to use leverage to get life insurance at a lower price by using the bank’s money. Understanding this, there’s another marketing aspect to premium financing that has never made sense to me, and we’ve been warning people about it for years. This entails financing premiums under the guise that doing so will multiply your returns on a cash-focused life insurance purchase.

In other words, you borrow money to purchase whole life or indexed universal life insurance policy to use it as a retirement income play. Instead of paying the premiums with your own money, you borrow a much larger amount of money and use it to extract additional gain from dividends or indexing credits provided by the cash accumulation features of the life insurance.

Insurance agents frequently use examples of borrowing money to make investments to frame their pitch for this type of life insurance sale. A common example is a real estate investor who borrows money to buy a house that she then flips and sells for, say, $300,000. Her investment was the $40,000 down payment she made on the loan she used to buy the house in the first place. This gives her rate of return the appearance of being astronomical, and in fact, this does work to some extent with real estate.

However, life insurance is not the same as real estate. For at least a few decades, no one will borrow any amount of money to pay life insurance premiums and generate cash surrender value close to the borrowed amount. I’ve frequently argued that we should consider the option of simply paying the premium out of pocket, and I’ll use the following example to demonstrate my point.

Assume a bank is willing to lend you $100,000 at 6% interest per year while also extending the loan on a zero-coupon basis with a 20-year balloon payment. Yes, I understand that such a loan is unusual today, but stick with me because this example highlights the key point behind premium-financed life insurance in the context of cash accumulation.

At the same time, you are confident that you can take this $100,000 and earn an 8 percent annual return on investment. So you borrow the money and everything goes exactly as planned. Your loan balance at the end of 20 years is $320,713.55. Your investment, on the other hand, is worth $466,095.71. As a result, you can repay the loan and pocket $145,382.17. This move necessitates no out-of-pocket expenses on your part. To accomplish this, you simply need to sign the loan application and accept the risk as a borrower. You’d be foolish not to take advantage of such an opportunity if it presented itself. This is an example of how to use leverage to increase your net worth.

These figures appear impressive, but when using this example to sell the concept of financial premiums for a life insurance policy, we need to use more realistic figures to determine whether the juice is worth the squeeze. Assume the loan now has a 2% annual interest rate and your “investment” will grow at 4% per year for the next 20 years. You will have $70,517.57 after repaying the loan. This isn’t bad, but it’s less than half of what you’d have if you followed the previous example.

Premium Financing Risks

- Rising Interest Rates

When you borrow money for premium financing, the interest rate can go up and down. If it goes up a lot, you might have trouble paying it back, and any investment gains you make might not be enough to cover the higher interest.

- Financial Sustainability

These loans usually last 3 to 5 years, and you’ll want to renew them to keep investing your money. But, at renewal time, the lender checks if you can still pay back the loan. If they think you can’t, they might increase the interest rate or deny you the loan.

- Insufficient Policy Growth

Life insurance policies grow through interest and investments. Sometimes, they don’t grow as expected. If that happens, the collateral you put up loses value, and you might have to give more collateral to avoid defaulting on the loan. If you die, and the insurance payout isn’t enough to cover the loan, your other assets might have to be used to pay it off.

In simple terms, taking a premium financing loan can be risky because interest rates can go up, your financial situation can change, and your insurance policy might not perform as well as expected. If things don’t go as planned, you may have to provide more collateral or use your other assets to pay off the loan.

The Bottom Line

Life insurance simply cannot generate enough return in a short enough period to make borrowing money to extract a slightly higher return worth the risk of financing the premiums. Some disagree, but after many conversations with them, I’m convinced that they don’t fully understand the risks associated with such an arrangement.

Finally, life insurance is intended to be a secure means of accumulating wealth. It’s supposed to be a reliable asset allocation strategy. One that does not expose you to the risk of losing your principal. In this context, introducing premium financing takes an otherwise safe asset with a reasonable return and dramatically skews the risk/reward ratio heavily against the policy owner.

Expert Life Insurance Agent and health insurance agent

Dylan is your go-to guy for life and health insurance at InsureGuardian. He’s helped over 2,500 clients just like you figure out the best insurance plans for their needs. Before joining us, Dylan was sharing his expertise on TV with Global News and making a difference with various charities focused on health. He’s not just about selling insurance; he’s passionate about making sure you’re covered for whatever life throws your way.